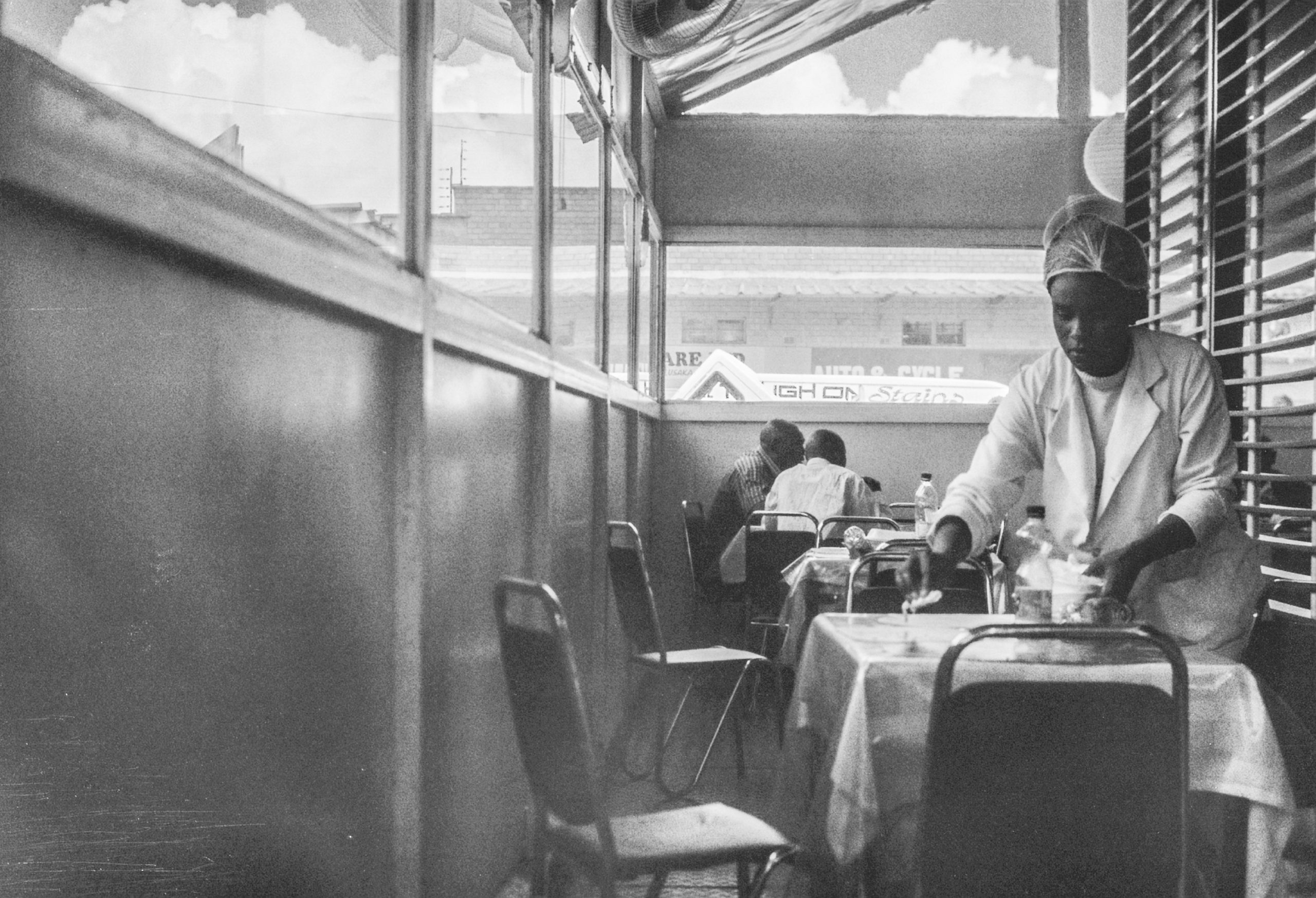

Our theme of late has focused on roadside Lusaka – our images have been more candid than anything, attempting to portray that decisive moment so essential in street-photography. These moments are first and foremost aesthetically appealing, an attempt to depict some semblance of artistic form. They go beyond form, reaching into the realm of human behavior – street photography feeds on the life behaviours of its subjects. Like a psychologist the camera attempts to understands patterns, both hidden and manifest, of humanity. However, the roadside is only one way to experience life – it is essentially to experience the outside world. It attempts to grasp the public performance of our daily rituals; but what of our private rituals?

Perhaps then, it is necessary to shift the focus entirely – this time to the interior. So our next theme is the interior of Lusaka. For us, the inside constitutes the mundane such as the chair at a dining table, the portrait of Jesus next to a clock or a peek through the window. In truth, there is no limit to the variation of the inside in the same way that there is no limit to the variation of the outside. But what is ‘the inside’? Practically speaking, the inside is a space surrounded by walls with a roof overhead; even the simplest of dwellings have this basic architectural description. But philosophically speaking, the inside assumes an entire metaphysical universe – we associate the inside with a place of comfort and privacy, a place of security where we can be one with ourselves. Whilst the outside is a place of danger, we must be on guard – they are trying to get me, after all.

What are the implications for photography? Or rather, how does photography play a role in all of this? Early on, during the 19th century, photography developed as an outdoor activity; its technology required such a setting – a relatively long period of exposure to light was needed in order to produce a usable image on a photographic plate. It was only at the turn of the 20th century that flash photography became widespread, thus the ability to photograph indoor subjects extensively. The first major flash photographic publication was How the Other Half Lives by Jacob Riis, a book which photographed the poor in their tenements in the slums of New York, bringing widespread attention for the need of social reform in the city. Thus, ironically, the first large-scale photographing of the interior was a documentation of its depravity, not its comfort.

Our ambitions are a little lower than pioneers such as Riis; instead, we simply intend to state that the ‘inside’ is photographable precisely because it consumes so much of our everyday life. It is not a wedding, a baby-shower or a funeral, and that is precisely why it is important. We seem to attach so much importance to these rare events, but how much do they actually tell us of our lives? Perhaps a wedding can give us a glimpse of happiness and a baby shower a glimpse of hope, but it will never be able to supplant the unassuming, everyday happiness and hope of having a picture of Jesus next to your wall clock.

And this is precisely the power of the everyday – it is unassuming. It is the actual manifestations of our desires, not the hopeful fulfillment of them. It is time we assume the unassuming. In good taste, too.

Sebastian Moronell.